McLemee on James on The Sopranos

In 6 seasons over 10 years, “The Sopranos” has confirmed again and again C.L.R. James’s point about the gangster as an archetypal figure of American society. But the creators have gone far beyond his early insights. I say that with all due respect to James’s memory--and with the firm certainty that he would have been a devoted fan and capable interpreter.

--Scott McLemee, at Inside Higher Ed, explaining how C.L.R. James's American Civilisation can help us understand The Sopranos--yes, really. (I've always been grateful to Scott for his review of Letters from London published in Bookforum in 2003).

Dear readers: For our sixth anniversary in May 2010, The Caribbean Review of Books has launched a new website at www.caribbeanreviewofbooks.com. Antilles has now moved to www.caribbeanreviewofbooks.com/antilles — please update your bookmarks and RSS feed. If you link to Antilles from your own blog or website, please update that too!

Saturday, 9 June 2007

Friday, 8 June 2007

Making it up

Judy Raymond, Caribbean Beat editor and sometime CRB contributor, on Jean Rhys and the "personal art" of make-up.

At university, fascinated by theatre but too timid to act, I did stage make-up. I plunged in at the deep end, turning undergraduates into pensioners, making them up to play in a musical about death that was set in an old people’s home. It was called The Dark, it was as bad as it sounds, and I don’t think it even ran for the full week at the Oxford Playhouse. But it taught me to work with greasepaint and do wrinkles. Later I learned kabuki make-up, for a production of West Side Story; and I grappled with artificial hair to give Dogberry a fearsome set of mutton-chop whiskers in a Victorian-style production of Much Ado About Nothing, staged in Trinity Gardens.

You give a 20-year-old wrinkles by using a blend of dark brown and crimson lake greasepaint sticks, mixing it on the back of your hand and applying it, swiftly, in as few strokes as possible, with a paintbrush. To make them realistic, you tell the actor to smile or frown, and the natural fold lines of those expressions will remain a few seconds after, long enough to trace them firmly with your brush. Those faint creases are where their real wrinkles will form, sneakily, over the years.

The dress rehearsals were the best: that was the first time you did the make-up, and it was a huge boost to the teenage cast’s confidence when they were suddenly made to look the part of the middle-aged tyrant or the bumbling constable they were required to impersonate.

That was when I first started wearing make-up seriously--except that it wasn’t entirely serious, because there’s always an element of play in it: who shall I be today? How would I look with lizard-green lids, or scarlet lips? It was more fun then, in the 80s, when you could paint on goth eyes with heavy kohl liner and charcoal eyeshadow, or venture out in green eyeliner and blue-and-silver eyelids . . . and have them much admired.

Nowadays, though, wearing too much make-up would make me look both older and less grown-up. Slap, the English call it. I wouldn’t want to look like an old slapper. But I still wouldn’t leave the house without it, out of an unsavoury, neurotic mix of vanity and its opposite. Even if I’m just buying milk at Hi-Lo, in my uniform of white t-shirt and jeans, my eyeshadow (a smudge of taupe) comes too.

Putting on make-up is still a form of playing dress-up, though my disguises now have to be more subtle. The ideal now, in this day and my age, is to look as if you’re naturally lovely but just happen to be wearing a touch of make-up, and not like a mistress of that most frivolous art.

Because, like fashion, it’s not considered a real art. Make-up is superficial, ephemeral, in the most literal sense. So I felt guilty when I arrived home the other day with not one but three new lipsticks. I’m appalled, honestly, to find I now own 27 (just did a spot of research there). That isn’t rational. This is an addiction, though a minor one.

But it also happened partly because I’m still in search of the perfect pink: not as deep as rose, as bright as bubblegum, or as inconspicuous as nude (you see the difficulty). One of the new ones has turned out to be a bright coral, which I’ll probably never wear, except for some special effect, like the creamy matt pale pink one I only use for a 60s look, with no blusher, ivory eyelids, and lots of black liquid eyeliner.

. . . But I digress. One of the reasons make-up is thought frivolous, and frowned upon by certain varieties of feminist, is because it’s thought to be for the viewing pleasure of men. Well, up to a point. Yes, women are seen, looked at as objects in ways that men are not--not necessarily sexual objects, though, but aesthetic ones. And self-adornment by people of both sexes may be the oldest of the applied arts. The hard truth, too, is that looks matter, and beauty, and the human concern with beauty, were not invented by men.

If you’re the sort of person who’s interested in the other arts, who cares about books and music and paintings and the look of the space you live in, it’s a logical extension of that concern to practise a personal art, with yourself as a canvas. Indeed, make-up is a most perfect form of self-expression, with yourself as not only the artist, but also both the subject and the object of your art. (Take it a little further and you become Cindy Sherman.)

Make-up improves on what nature gave you, and thus makes you look more like your real self. And yet the face you paint on is also a mask; which may be not only a disguise, but also a form of protection.

I think of the poignant photos of Jean Rhys as a very old woman, so obviously desperately sad, so carefully made up, and still beautiful.

She too would have learned about make-up in the theatre, when after leaving school she tried to be an actress. She became a chorus girl, but she was always terrified of the audience, and soon gave up the stage.

But in the dazzle of the naked bulbs that ringed the dressing-room mirrors, Rhys had discovered the uses of make-up. You come out of the cold outside world into the shabby intimacy of backstage, where with the rest of the cast you conspire to deceive the audience. Behind the bogus backdrops of the set, between the bare walls and harsh lights, you put on a new identity, in borrowed clothes and, thinner but more effective, a layer of greasepaint that covers the fear.

In those days nice girls didn’t paint, but in any case Rhys soon slipped below the threshold of respectability. A lover recorded in 1915 that she spent hours in front of a mirror, “combing out her lovely hair and playing with a make-up box filled with a variety of unguents, powders and lipsticks.”

She was 25 then, and didn’t need it to make her beautiful. She shouldn’t have needed it at 80. But this is how the novelist David Plante draws her in old age, in a picture as careful as it is cruel.

“Her make-up was hit-and-miss,” he writes. “There were patches of thick beige powder on her jaw and on the side of her nose, her lipstick was as much around her lips as on them, the marks of the eye-pencil criss-crossed her lids, so I thought she might easily have jabbed it in her eyes.”

By then, at last, Rhys was being feted as a great writer, thanks to her last and best novel, Wide Sargasso Sea. She had money to extend and heat her tiny cottage, to pay for nice clothes and trips to see new friends in London (among them Lady Antonia Fraser, also a writer and a beauty who took pleasure in that beauty). Why would Rhys feel the need to daub herself in this clumsy way, so that Plante could portray her as a clown?

Because she had so much to hide, although she revealed so much of herself in her fiction. Crippled by childhood wounds, Rhys had never learned the skills to cope with life. Very early on, she’d been afflicted by a profound loneliness that lasted through three marriages. She’d outlived three husbands, failed as a mother, endured poverty for decades. She met with success as a writer when she was an old woman, too late to enjoy it.

Her beauty was a shield and a consolation, though it didn’t make her life easier in any material way. Restored by make-up, it gave her a way to face the world.

--JR

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

12:00 pm

1 comments

![]()

Quick links

- Kwame Dawes on his "first real influence", Gerard Manley Hopkins.

- Marlon James on running afoul of US immigration.

- Geoffrey Philp on his new children's book, Grandpa Sydney's Anancy Stories.

- Nalo Hopkinson on where you can buy her handicraft online--latest item on offer is a music box.

- Tishani Doshi (at the UK Guardian books blog) on poetry at the Hay Festival, including this brief mention of Derek Walcott's appearance:

Only the previous night, I'd watched Derek Walcott receive a standing ovation in the very same tent when he recited, quite emotionally, Walter de la Mare's "Farewell". One woman in the audience requested that he read his own "Love After Love" because it had a special place in her heart. And he did.

- And Randy Kennedy (in the New York Times) on Felix Gonzalez-Torres, the late Cuba-born, Puerto Rico-raised (i.e. Caribbean) artist who is representing the United States at this year's Venice Biennale.

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

11:39 am

1 comments

![]()

Thursday, 7 June 2007

Embah: La Vie

Detail of La Vie (2006, 29 x 50 inches, mixed media on wood panel), by the Trinidadian artist Embah, whose work is currently showing (until 14 July) at the White Columns gallery in New York.

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

12:51 pm

0

comments

![]()

"I will tell you..."

“I will tell you,” I said firmly. “They do not have baby.”

(No direct connection with Caribbean literature, but I couldn't resist.)

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

10:09 am

0

comments

![]()

Wednesday, 6 June 2007

"They had simply gone elsewhere"

Marie Micheline went to live with my uncle Joseph and aunt Denise for the same reason that my brother and I did: our parents had disappeared. They had not abandoned us. Nor had they been imprisoned or killed by the henchmen of the dictatorship that had come to power in Haiti in 1957, when Marie Micheline was five years old and my parents had not yet met. They had simply, as my uncle explained first to her and then to us, gone elsewhere.

-- From "Marie Micheline" by Edwidge Danticat, an excerpt from her forthcoming memoir, published in the 11 June issue of the New Yorker.

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

11:14 am

0

comments

![]()

Tuesday, 5 June 2007

Who's counting?

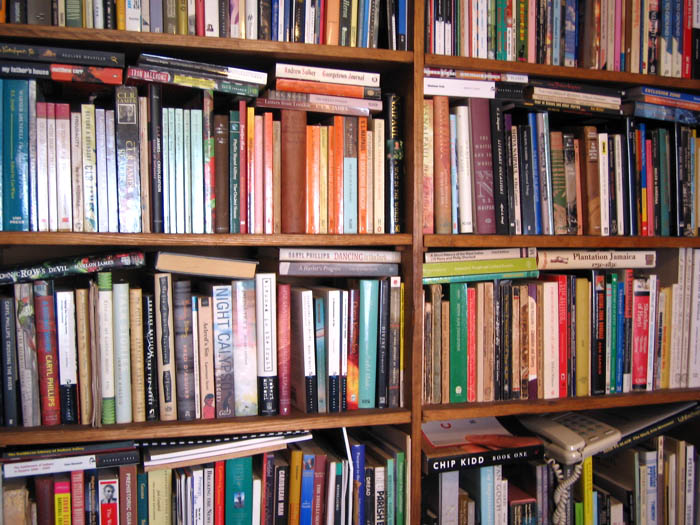

This throwaway comment by Fran Lebowitz--quoted over at Gawker, in a post about the 80th birthday party at the Strand, my favourite used book shop in New York--got me thinking:

Fran Lebowitz got off a good line about wishing the Strand was her apartment, and how New York is divided into two groups of people: "people with five thousand books and people with the space for them."

Five thousand doesn't seem an unreasonable number of books to have amassed by early middle age over the course of a readerly life, does it? By my rough estimate, the shelves in my small study can hold about two thousand books comfortably, so if I factor in the overflows onto floor, desk, and other items of furniture, there might be almost 2,500 books close to hand as I sit here typing.

There is another bookcase in the corridor outside--well, two, but one is full of magazines--and another in my bedroom. Somewhere in the house are about a dozen boxes of books in a more secluded form of storage--they include my shockingly large collection of ratty paperback detective novels, which I read avidly as a teenager. I recently discovered a stash of books in the freezer--double-Ziploc'd--where I'd put them months before in an attempt to end a powder-post beetle infestation. I don't think I'd have the energy to do a proper book census even if I wanted to, but a safe guess would be that I own about 3,500 books, in varying stages of moulder, decay, and consumption by insects.

Have I read them all? Hardly. I own hundreds of books, probably, that I'll never get around to reading, but it's nice to have them handy just in case. I also own many duplicate copies--two full sets of Jane Austen, for instance, just by chance. And many reference books or scholarly volumes I might dip into once or twice, in search of some abstruse fact, but which I'll never read cover to cover. And many many books I've already read, will probably never read again, but which I have no intention of discarding. I've never understood people who give away books once they're "done" with them. Are you ever really "done" with a book? If there's even the smallest chance you may re-read it someday? And isn't it in some sense comforting--physically comforting--to have books around?

And why--surrounded by books, as I clearly am--indeed, tripping over books, as I occasionally do--does it so often seem I have nothing to read?

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

12:44 pm

2

comments

![]()

Danticat on Díaz

"It's one of those stories that you like in spite of yourself. You think ... I shouldn't really enjoy this character, but you do." --Edwidge Danticat, discussing Junot Díaz's short story "How to Date a Brown Girl (Black Girl, White Girl, or Halfie)" with New Yorker fiction editor Deborah Treisman, in this month's New Yorker Out Loud podcast.

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

12:09 pm

0

comments

![]()

Monday, 4 June 2007

Last taste of Calabash

Is it really a whole week, dear readers, since I returned from Jamaica and the Calabash International Literary Festival? Here's a final roundup of Calabash 2007 coverage:

- Kwame Dawes, one of the three Calabash principals (with Colin Channer and Justine Henzell), has written a detailed account of this year's festival in a series of posts over at Harriet, the Poetry Foundation blog: arrival, day one, day two, and day three.

- At the UK Guardian books blog, Toby Lichtig writes about experiencing what he calls "a literary festival with a different flavour" (that flavour was rum punch and conch stew, from the sound of it).

- The Jamaican newspapers have understandably been full of Calabash coverage over the last week. Today in the Observer Tyrone S. Reid interviews Justine Henzell, and is bowled over by her charm.

- And the young Jamaican photographer Varun Baker has posted his Calabash photos at Flickr, joining the excellent selection already posted by Georgia Popplewell.

If I've missed any interesting Calabash coverage, either in blogs or in the mainstream media, I'd love to know. Please leave links in the comments below.

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

1:39 pm

0

comments

![]()

More bedside books

I know, dear readers, Friday is supposed to be "bedside books" day. But last Friday I was busy preparing for the "Finding the Thread" event and didn't manage to post anything to Antilles at all. Let me try to make good. Georgia Popplewell of Caribbean Free Radio hasn't written for the CRB in ages, but perhaps her contributing this list--of books she's taken on her nearly-three-week sojourn in Tobago--is a sign that she'll soon reappear in our pages.

Having returned from another trip only the day before, I had only a few hours to pack for my move over to Tobago, so among the many rapid decisions I was forced to make was selecting the 18 days' worth of reading matter I'd be taking along. On account of the volume of reading I do daily on the web, my rapidly worsening ADD, and my aversion to clutter, I've begun to limit myself to reading one book at a time (which I'm aware marks me as a weak-minded philistine), so when I'm at home it's unlikely that you'll find more than one tome at either my actual or metaphorical bedside at any given time. In a borrowed bedroom, however, you sometimes don't have a choice. Here are the books that made it over to Tobago in a box on the back seat of my car, and which now sit on my bedside table:

- Ruchir Joshi's The Last Jet Engine Laugh, which I'm in the middle of right now. One of the two or three best meals I had during my visit to Delhi last December was taken in the company of Ruchir, who also introduced us to the joys of masala peanuts, so I was curious to see what sort of novel this slightly mad, generous-spirited human would produce. So far it's a highly entertaining read, beautifully written, occasionally baffling. Set partly in the year 2030, one of its sub-plots speculates on the fate of Indian independence leader Subhash Chandra Bose, who may or may not have died in a plane crash over Taiwan in 1945.

- Irène Némirovsky's Suite Française. I'm yet to read a bad review, and I'm also fascinated by the circumstances of its creation.

- Modern Baptists by James Wilcox. I first read about this book, which was first published in 1983, in a 1994 New Yorker article which hailed it as a work of comic genius. 13 years later, I've finally got myself a copy.

- Everything is Miscellaneous by David Weinberger. Weinberger is on the Global Voices board of advisors, so he's sort of a colleague, but I'm also deeply interested in the ideas the book explores, which have to do with how shifting to the digital space changes how people think, organise and categorise. I'm also behind on my reading of the key texts on new media (which, after all, is the field in which I currently make a good part my living) so Miscelleanous is partly meant to kick me (backwards, it's true) in that direction. Ethan Zuckerman described the experience of reading the book, by the way, as ". . . a little like drinking a mojito - smooth going down, but deceptively powerful, and slightly staggering when you get up to buy the next round." As it so happens, I love mojitos.

Plus several weeks' worth of New Yorkers and a couple of books on photography, the other pastime that keeps me from reading more, notably Bryan Peterson's Understanding Exposure.

Thankfully, the house where I'm staying has a decent selection of books in case I exhaust the supply I've brought (highly unlikely) or feel in the mood for something else, but there are two books I wish I'd put in that box in the back seat of my car:

- Maryse Condé's biography Tales from the Heart, which I picked up last week at the Calabash Literary Festival after hearing Condé's husband and translator, Richard Philcox, read an excerpt. The only Condé work I'd read previously was La vie scélérate, which didn't bowl me over, but the biography sounded interesting, and I've found myself wishing, lately, to re-connect with the French Caribbean.

- And A Matter of Taste: The Penguin Book of Indian Writing on Food, because you should never leave home for 18 days without a book of essays, and because it might inspire me to do some actual cooking while I'm here.

--GP

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

1:20 pm

0

comments

![]()

Sunday, 3 June 2007

Sunday links roundup

- The Arts and Leisure section of today's Jamaica Gleaner offers a review by Mary Hanna of Erna Brodber's new novel, The Rainmaker's Mistake, as well as two short stories: "Sailing from DaMarie Street", by Kimmisha Thomas, and "The Day That Thou Gavest", by Cordella Lewis.

- Also in the Gleaner, Anthea McGibbon reports on a show of Jamaican art, "dominated" by David Boxer and Milton George, at the Pan American Art Gallery in Miami; and Jonathan Greenland, director of the National Gallery of Jamaica, interviews artist Stafford Schliefer.

- In the Stabroek News, Al Creighton reviews Panorama: A Portrait of Guyana, the annual Independence show at the National Gallery of Guyana; and Ian McDonald asks, What is the relevance of poetry? Pure enjoyment.

- Who has Edwidge Danticat been reading lately? J.M. Coetzee and Nikki Giovanni, according to a feature in today's New York Times Book Review, in which various writers are asked about their recent reading choices.

- At the Poetry Foundation blog, Kwame Dawes writes about "copyright matters", in response to a question by Kenneth Goldsmith.

- Geoffrey Philp remembers Don Drummond with a podcast of Mervyn Morris's poem "Valley Prince".

- And Caribbean Free Radio posts the June tour schedule of Antiguan writer Marie-Elena John, who will be making appearances in and around Washington, DC, and New York in the coming weeks (read a recent interview with John, posted a couple of weeks ago on Antilles).

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

1:16 pm

0

comments

![]()