Dove

A poem by Shara McCallum, which appears in the anthology New Caribbean Poetry, edited by Kei Miller and published in May 2007 by Carcanet Press.

Imagine if you could have either cherry or stove,

but not both; if the sound of rain

would not answer to its name: tap, tap, pitter pat.

If one morning you woke and had to say dove,

not love, and mean it. If this went on

all through the day and night and into early dawn--

this calling of the world and all its parts

a single word: your cat's meow,

the kumquat freshly washed at the sink,

the milk bottle in the fridge, swallows

outside listing on the wind, the grey slant

of falling rain, a lover's hand grazing your neck.

New Caribbean Poetry: An Anthology includes the work of eight poets: Christian Campbell, Loretta Collins, Delores Gauntlett, Shara McCallum, Marilene Phipps, Jennifer Rahim, Tanya Shirley, and Ian Strachan. In his introduction to the collection, editor Kei Miller writes:

At a recent "Gathering of Writers" held at the Mona campus of the University of the West Indies, Derek Walcott declared that Caribbean poetry was only just beginning. The greatness was yet to come. The eight poets featured here are perhaps a small representation of "New Caribbean Poetry", but they are among the best. Their work is often featured in regional journals; they have been winning prizes; indeed, it is their names that are often called when one asks the question, what’s good and new in Caribbean poetry? For despite "the waters between us", poets in the region are often separated by no more than one or two degrees of separation. Along such small chains word quickly stumbles back about who is writing exciting things. These eight are; they are the beginning of Walcott’s prophecy.

Dear readers: For our sixth anniversary in May 2010, The Caribbean Review of Books has launched a new website at www.caribbeanreviewofbooks.com. Antilles has now moved to www.caribbeanreviewofbooks.com/antilles — please update your bookmarks and RSS feed. If you link to Antilles from your own blog or website, please update that too!

Saturday, 2 June 2007

Thursday, 31 May 2007

Finding the Thread

Alice Yard, Woodbrook, Port of Spain. Photo courtesy Ivan R. Belcic, Trinity College, USA

Finding the Thread: A Visual Arts Conversation will be hosted by architect Sean Leonard at Alice Yard, 80 Roberts Street, Woodbrook, Port of Spain, Trinidad, on Friday 1 June at 6.30 pm. Admission is free and all are welcome.

Writer and researcher Anne Walmsley and artists Stanley Greaves and Christopher Cozier will have an open discussion, introduced and moderated by CRB editor Nicholas Laughlin, finding the thread that connects the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM), founded in London in 1966, with regional conversations of the 1970s derived from Georgetown, Guyana, and recent initiatives in the visual arts.

Alice Yard is Sean Leonard's great-grandmother's backyard--an informal outdoor space with which he has been experimenting. Four generations of children played and imagined in that yard, and now Leonard wants to continue this tradition.

For more information, call (868) 622-6361.

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

3:50 pm

0

comments

![]()

"It is an extensive shore...."

Ah, that old, knotty, unknottable question: what does "Caribbean" mean? Over at Global Voices, Karel McIntosh asks three bloggers--Jamaicans Geoffrey Philp and Francis Wade, and the pseudonymous Guyana Media Critic--for some possible answers. Editing a magazine called The Caribbean Review of Books means, of course, that in all sorts of ways, theoretical and practical, I'm picking away at the question all the time. Which places are Caribbean and which are not? "You could even extend the definition to places in North America such as the recently colonized Miami and the older cities in Louisiana and the Carolinas or Plantation America," Philp suggests. Which immediately brings to mind the famous opening paragraph of Lloyd Best's seminal essay "Independent Thought and Caribbean Freedom":

When we think of the Caribbean we have in mind a canvas larger than that usually found in the gallery of the colonial mind. Certainly it includes the Antilles--Greater and Lesser--and the Guyanas. These together form the heartland of the system which it is our expressed purpose to change. But many times the Caribbean also includes the littoral that surrounds our sea. Admittedly, it is an extensive shore. And the contours which may be taken to mark it off are still--to an uncomfortable degree--a matter of personal taste. Yet our choice of boundaries is not, for that fact, baseless. For what we are trying to encompass within our scheme is the cultural, social, political and economic foundations of the "sugar plantation" variant of the colonial mind. Hence we sometimes include Carolina and Caracas with Kingston and Chacachacare, Corentyne and Camaguey; Recife with Paramaribo, Port of Spain and Pointe-a-Pitre; and British Honduras with Blanchisseuse and Barranquitas.

Which in turn prompts me to wonder: now that Lloyd Best is no longer with us, how soon will we get the volumes of his collected writings on politics, art, literature, and society that are so desperately missing from our bookshelves? Lloyd always resisted collecting his work into books, preferring to publish in newspapers and journals and magazines that were more accessible to the ordinary reader, and preferring the gradual evolution of ideas that long-term serial publication makes possible. But surely the time has now come to begin the massive task of collection into bound volumes that will ensure the permanent accessibility of his polymathic intelligence?

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

1:17 pm

2

comments

![]()

Wednesday, 30 May 2007

Underrated?

New York magazine asked 61 book critics to name their "favourite underrated book of the past ten years", and the full list, with brief annotations, is published in their current issue. I scrolled through, wondering if any Caribbean books would make an appearance--and there, nominated by Jean Stein, was Patrick Chamoiseau's Texaco.

I'm wondering, dear readers, what a "best underrated" list restricted to Caribbean books would look like. Off the top of my head, my choice would probably be Charlotte Williams's memoir Sugar and Slate, a nuanced story of the author's struggle to come to terms with her divided heritage--Welsh and Guyanese--and to understand the meanings and possibilities of "home". Identity, dividedness, and exile are classic themes in Caribbean literature, but Williams tackles them from what feels like a fresh perspective; and then there is the particular interest of her take on her father, the celebrated Guyanese artist and writer Denis Williams. (I wrote a very short review of Sugar and Slate some years ago.)

What would your "best underrated" Caribbean books of the last decade be, dear readers? Let us know in the comments below.

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

11:25 am

2

comments

![]()

Tuesday, 29 May 2007

"Where are the thinkers of today?"

While I was having a ball last Friday night in Treasure Beach, back in Port of Spain, CRB contributor Jonathan Ali went to hear Rex Nettleford, vice-chancellor emeritus of the University of the West Indies, deliver the Eric Williams Memorial Lecture. He files this report on the event.

Jamaica’s Rex Nettleford is a well-known scholar, historian, and political analyst. His achievements and accolades in these fields over the many years of his career are numerous; and he is rightly considered one of the foremost intellectual figures of the Caribbean. Yet when I think of Professor Nettleford, it isn’t so much his mind that I consider, but rather his feet.

You see, in addition to his other achievements, Nettleford is also the founder, artistic director, and principal choreographer of the prestigious National Dance Theatre Company of Jamaica. And although I was at the Central Bank Auditorium in Port of Spain last Friday evening to hear him speak--the first time I was to be so privileged--I’d be lying if I said a part of me didn’t wish to see the august professor do a few dance moves as well.

The occasion was the 21st Dr Eric Williams Memorial Lecture--Eric Williams, of course, was the first prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, as well as an historian and scholar of note. Past speakers in the series have included Nobel Laureates Sir Arthur Lewis of St Lucia (in the inaugural year) and India’s Amartya Sen (in 2001--I’m still kicking myself for missing that one).

(An aside: only two out of the 21 speakers in the lecture series thus far have been women. I say nothing else here except that the organisers might want to have a look at that.)

Nettleford’s topic was “Slavery and Education in the Caribbean: Mask, Myth and Metaphor”. No doubt the first word of that title would have a few people shaking their heads and groaning, “What, again?” Yet it was the third word that held my interest. What would Nettleford have to say about how we have used that all-important tool of education in setting about to repair the almighty damage done by slavery and colonialism that was new, that was different?

Dressed elegantly in black--black trousers, black buttonless dress shirt with a rounded neck--Nettleford cut a noticeably different figure to the many dignitaries (including Prime Minister Patrick Manning) in their jackets and ties. He stood with both hands at either side of the lectern, as if in an act of balancing, and it appeared to me--my companion and I were sitting to the right of the stage, almost in line with the podium, so we could see his entire body--it appeared to me that he was swaying ever so gently, from side to side, rhythmically, as if to some silent metronome.

Nettleford isn’t the greatest rhetorician, yet he does possess a finely modulated voice, not especially Jamaican in its accent (I was reminded of V.S. Naipaul’s assertion that Jamaicans speak the “purest English” of all West Indians). He spoke as a man who has considered long and hard the question of the Caribbean, what exactly it is, and what has gone into making it what it is. His references ranged far and wide, from Jesus Christ to Jimmy Cliff, and more traditionally scholarly points.

Yet for all that, I came away with a vague sense of dissatisfaction. For a start, he limited his definition of education to the traditional forms of knowledge and experience passed down by the peoples, chiefly African, who came to populate these territories over the past five hundred years. There was no discussion of formal education, its uses and misuses, how well it has served us, and how far it has failed to take into account our Caribbean reality. This was interesting, considering formal schooling for the masses was one of the major concerns of Eric Williams (to whom Nettleford often referred).

One of Nettleford’s arguments--perhaps his main thesis, you might say--was that the knowledge passed down by our forebears--in oral storytelling, in music, traditional medicine and so on--have gone into creating our Caribbean culture, giving us our identity. Hardly a novel idea, and one that fails to take into account the contemporary challenges of identity being faced by the Caribbean by various forces, internal as well as external--though there was reference to globalisation and its effects.

There was, also, some talk of politics. Speaking on the issue of resistance, and the modes of resisting their condition the slaves engaged in that live on in today’s free society in various forms, Nettleford noted that Caribbean politicians (who, he hastened to add, have both his respect and sympathy) have great experience in “knowing how to make things not work”. This elicited some laughter from the audience, but not much.

It was undoubtedly a pleasure to hear from one of the few great Caribbean minds--with the recent death of Lloyd Best, their numbers are even fewer now, and needed no less than ever. Yet it occurred to me, as we left the auditorium to repair for food and drinks, that these minds are almost to a person of an older generation. They came of age in that heady time of the promise of independence; their ideas, as revolutionary and important as they were then, are in need of being modified, added to, by those of the post-independence generation, to serve our contemporary Caribbean. Where are the great scholars and thinkers of today? Without them, the work of Rex Nettleford and others could well end up being for naught.

-- JA

Rex Nettleford performing in 1965; photo by Maria LaYacona

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

10:55 am

2

comments

![]()

Caribbean lit links

- Over at his blog, my colleague Jeremy Taylor describes the feeling of "book fatigue"--"So many books I've started in the last few weeks, only to abandon them after a few chapters or pages, or skim through them impatient to get to the end!"--then lists the handful of books that have managed to hold his interest in recent months.

- And over at his blog, Marlon James writes an impassioned post about "the white man in Africa", inspired in part by Peter Godwin's book When the Crocodile Eats the Sun.

The Godwins may have been after all, good people trying to live, making a home where they had hung their hat. But a part of me will always see them as interlopers and if they did not risk anything to make Africans’ lives better then they were silent participants in making it worse. Why should I care about another story that tries to make the white experience in Africa compelling?

- In the Jamaica Gleaner, Mel Cooke reports on the opening night of Calabash, with a review of Roger Guenveur Smith's Who Killed Bob Marley?--as well as the Saturday night party.

- In last Sunday's Stabroek News, Al Creighton writes about the anthology of Guyanese poetry edited by A.J. Seymour and published as a special issue of Kyk-over-Al in 1954.

- And last weekend's Guardian Review publishes Derek Walcott's lovely early poem "Prelude", well known to readers in the Caribbean but perhaps less so to those elsewhere.

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

10:39 am

0

comments

![]()

Sunday, 27 May 2007

Sunday at Calabash

The main tent at Jake's

I'm back in Kingston as I write this post, dear readers, on the other side of a three-hour drive from Treasure Beach. I would gladly have stuck around for the final hours of Calabash and the Commonwealth Writers' Prize party beside the pool at Jake's, but I have to be at the airport in the morning.

Distracted by a bowl of ackee and a plate of Johhny cakes, I got off to a late start today, and missed the first part of the 50th anniversary reading of The Mystic Masseur--the section read by former Miss World Cindy Breakspeare (I'm told she was the best of the four readers). I took my seat about halfway through Peter Bunting's section, and was impressed by the way he handled, in his Jamaican accent, Naipaul's pitch-perfect Trinidadian English. The other two readers were less successful, at least to my Trinidadian ear. (Note to Calabash organisers: next time, ask a Trini to read! There were enough of us in the audience.)

After that reading I wandered off in search of today's Jamaica Observer--I wanted to see the piece on the CRB that appeared in the Bookends section. But apparently the Observer doesn't make it down to Treasure Beach--there were none in the shops, none in the lobby at Jake's, none tucked under anyone's arm. By the time I gave up and returned to the main tent, Kendel Hippolyte was going up on stage. My timing was perfect. I'd never heard Kendel read, and though all the chairs in the front rows were taken, a low tree near the stage offered an excellent, breezy vantage point.

Then came the event we'd all been waiting for--or, at least, the event all the Commonwealth Writers' Prize finalists were waiting for: the announcement of the prizes. There was much speculation about whether the writers already knew the results or not, and jokes about a betting pool (at least, I think they were jokes). I snagged a front-row seat, then gave it up for one of the judges. The prize ceremony was a model of brevity. I thought D.Y. Béchard looked insufficiently surprised to win the prize for best first book--perhaps he'd done some googling this morning?--but Lloyd Jones seemed genuinely taken aback, even flustered. Then all the writers, winners and losers, went off for stiff drinks, and I went off to our villa to pack my bags.

And that, dear readers, was Calabash 2007. The best part of the weekend, even better than any of the actual events on the programme, was the chance to spend time with friends--writers and otherwise--who I don't get to see often, and the chance to finally meet a few writers who I've read and corresponded with, like Kei Miller and Marie-Elena John. I return home tomorrow with a tan, a copy of Michael Ondaatje's new novel, and a plan to return for Calabash next year. And maybe I'll bring an even bigger Trinidadian contingent.

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

11:05 pm

0

comments

![]()

Kwame Dawes on Calabash

Somehow, in between actually running the Calabash programme, Kwame Dawes has found the time to blog about the festival this weekend, over at the Poetry Foundation blog, Harriet. Read his two instalments thus far: "Arrival" and "First Night".

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

10:22 pm

0

comments

![]()

Saturday evening at Calabash

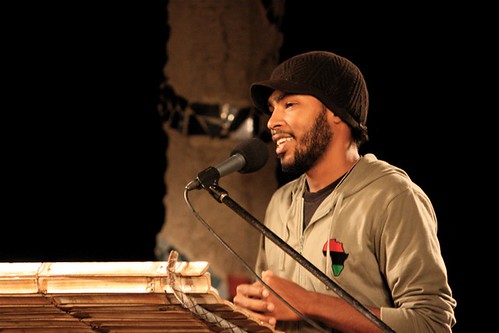

Trinidadian poet Muhammad Muwakil performing at the evening open mike session

Last evening's tripartite reading by Maryse Condé, Michael Ondaatje, and Caryl Phillips--billed by the Calabash organisers as "Supersize me!"--was the festival's most popular event thus far. The main tent was crammed with people who seemed undaunted by the torrents of rain lashing outside. Sitting near the right-hand side of the tent, I had to use an umbrella to shield me from horizontal gusts.

I barely noticed the discomfort. All three writers were in top form. Condé spoke for a few minutes in a powerful, heavily accented voice before her husband and translator, Richard Philcox, read two selections from her work. Then Ondaatje jogged up to the stage, protected by a raincoat. He read "The Cinnamon Peeler's Wife", perhaps his best-known poem, and excerpts from Running in the Family, Anil's Ghost, and his new novel, Divisadero. (It struck me that his accent, though it contains South Asian and Canadian twangs, could pass for Trinidadian.) Finally, Caryl Phillips, dressed all in black, read the opening pages of his last novel, Dancing in the Dark, and his essay "Growing Pains", which I found unexpectedly affecting.

By the time Phillips had finished the rain had stopped, and the blank grey sky had turned a lovely shade of deep, dark blue--just in time for the day's second open mike session, moderated once again by Marlon James. I thought the performers were better and sharper, on the whole, than the ones at the earlier session, but I was utterly bewildered by the young man who recited, in a monotone, a poem called "Antidepressants for Life". The bravest performer was the Trinidadian poet Colin Robinson, who delivered an impassioned, moving poem about resistance to anti-gay prejudice.

And it was another Trinidadian who provided the evening's highlight. Young Muhammad Muwakil, a star of Trinidad's performance poetry scene, brought the house down with his witty, lyrically tricksy ode to an unnamed crush. When he went slightly over his three minutes and poor Marlon tried to cut him short, there were cries of "Leave him alone!", and Muhammad left the stage to thundering applause. Colin Channer actually interrupted the session to come on stage and give a loud and very Jamaican endorsement: "Bullet! bullet! bullet!" Muhammad was a very tough act to follow, and fortunately not many tried.

I'm sorry to say, dear readers, that I skipped out on the evening's final reading, by the four Commonwealth nominees for best book. I was starving. Back at our villa, a sort of informal after-party developed as my housemates drifted back, bringing various friends and acquaintances with them. Muhammad was there--he gave a private performance of his championship-winning Midnight Robber speech from last Carnival--as well as two of Jamaica's best younger writers, Marlon James and Kei Miller, and the very nice Carlin Romano of the Philadelphia Inquirer, who grilled me about the state of Caribbean literature (I had drunk three glasses of wine by then, and I hope I gave relatively coherent answers to his questions). By midnight I was almost asleep on my feet. And so to bed.

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

10:58 am

0

comments

![]()

And the winners are....

Hmm--did somebody let something slip? This press release, written in a PR agent's confident past tense, announces the winners of the two Commonwealth Writers' Prizes--which won't be officially announced until the awards ceremony this afternoon. The information is supposed to be embargoed, so I won't give the winners' names here. But posting embargoed information online, where it's freely available to anyone with access to Google, isn't very sensible....

Posted by

Nicholas Laughlin

at

10:15 am

0

comments

![]()